The plaintiffs (Moonbug) own the popular kids YouTube channel CoComelon. Moonbug’s videos have garnered more than 165 billion (with a “b”) views on YouTube, outstreaming Bad Bunny, Taylor Swift, and Drake combined. In 2021, Moonbug sued the defendants (Babybus), alleging that the defendants’ Super JoJo website included videos, characters and other content that infringed upon Moonbug’s copyrights. Last month, after a three-week trial in federal district court in the Northern District of California before the Hon. Edward M. Chen, a jury awarded Moonbug $23.4 million (with an “m”) in damages.

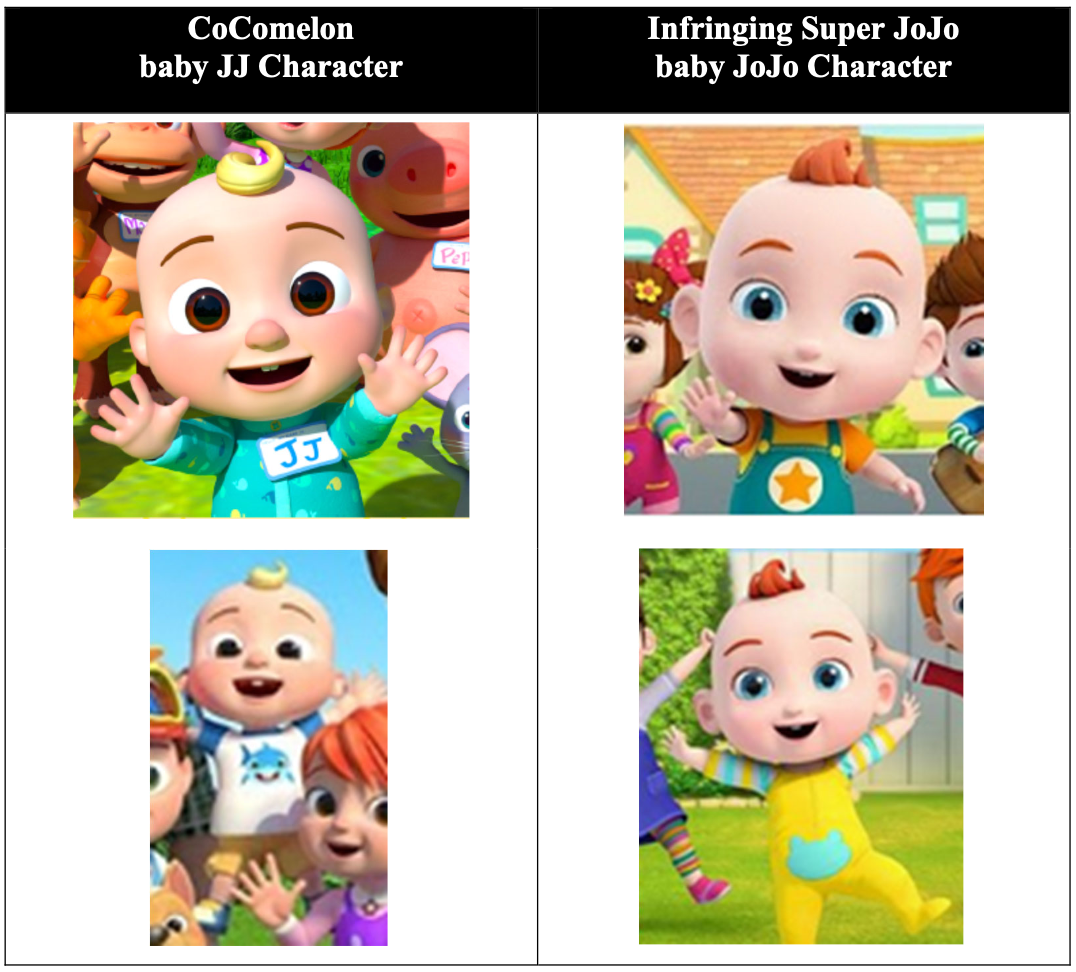

Among the issues in the case was whether the defendants' main character “Baby JoJo” infringed upon the plaintiffs’ character “Baby JJ.” Here are side-by-side comparisons from the complaint so you can judge for yourself:

In the Ninth Circuit, once it has been determined that the defendant actually copied the plaintiff’s work, courts use the two-part extrinsic/intrinsic test to determine whether that copying constituted unlawful appropriation (or infringement). The first (extrinsic) prong requires an objective analysis of the works to identify the elements in each that are protectable under copyright law. Expert testimony is permitted at this stage to help distinguish between protectable expression and unprotectable elements (such as ideas, public domain elements, and scenes a faire). Following this “analytic dissection” (or filtration), the similarities between the protectable elements in the works are compared. In the second (intrinsic) prong, the fact finder engages in a subjective analysis and comparison of the protectable elements of the two works from the standpoint of the ordinary reasonable observer.

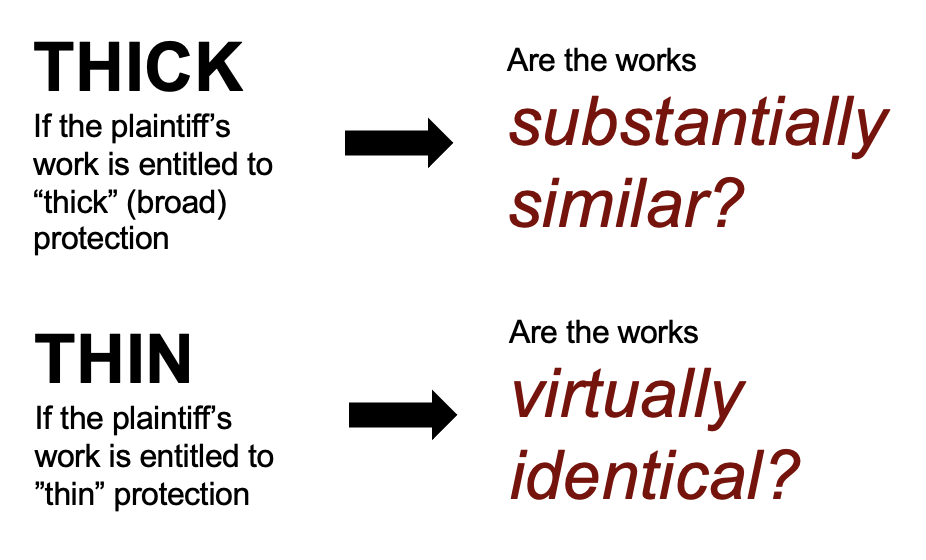

The standard the jury uses for these comparisons is dictated by the scope of protection to which the plaintiff’s work is entitled. As the court explained:

“If there’s a wide range of expression (for example, there are gazillions of ways to make an aliens-attack movie), then copyright protection is ‘broad’ and a work will infringe if it’s ‘substantially similar’ to the copyrighted work. ... In contrast, if there’s only a narrow range of expression (for example, there are only so many ways to paint a red bouncy ball on blank canvas), then copyright protection is ‘thin’ and a work must be ‘virtually identical’ to infringe.” (Cleaned up and citations omitted.)

When it came time to charge the jury, the parties fought about whether the Baby JJ character was entitled to “thick” or “thin” copyright protection and, thus, whether the jury should be instructed to use the "substantially similar" or "virtually identical" standard. The defendants argued that Baby JJ was entitled to only “thin” copyright protection since “the range of possible expression of baby cartoon characters in the chosen genre is narrow.” When creating a cartoon baby, they argued, an artist’s choices are dictated by the anatomy of a human child, and there are only so many different ways to draw a toddler's large, expressive eyes, chubby cheeks, short body, and that curlicue, mohawk hair thingamajig. The plaintiffs countered that Baby JJ deserved “thick” protection because it was a highly expressive work, resulting from numerous, creative, executional choices made by animators.

Which end of the "thick-thin" continuum a particular work falls is a "qualitative [and] relative" determination that "defies precise definition." And while the court noted that the determination in the instant case was "concededly not obvious," it ultimately agreed with the plaintiffs and found that Baby JJ was entitled to "thick" protection.

The court began by evaluating the range of creative expression possible when drawing baby/toddler-age cartoon characters:

“Even if there are visual elements common to babies in the genre (e.g., oversized head, big eyes, button nose), there are numerous creative decisions that could be applied to a multiplicity of physical elements. For instance, for Moonbug’s JJ character, Moonbug’s expert witness Mr. Fran Krause testified that “some elements from the design of JJ that I think are expressed in a creative way that are specific to this character” include JJ’s two front upper teeth, his specific head shape, rosy cheeks, shiny Playdough hair, little button nose, half-moon smile, doll’s eyes, solid eyebrows, and yellow and turquoise onesie. Other animators are free to design babies with different combinations of these creative elements. One such baby could have almond-shaped brown eyes, a full head of wavy black hair, a birthmark on her arm, sporting linen overalls, a signature paintbrush, and somewhat obstinate yet ultimately compliant demeanor. Another baby could have green eyes, freckles, pink hair, wearing a floral dress and bonnet, and with a shy and soft voice. Animators have the option to vary the babies’ physical traits of gender, ethnicity, race, hair color, hairstyle, physical proportions, clothing, and accessories.” (Cleaned up.)

The court took notice of the very different ways in which baby characters were rendered (whether in 2D or 3D) in Storks, My Neighbor Totoro, Moana, The Incredibles and others productions. And the fact that the defendants themselves had considered (and ultimately rejected) various redesigns of Baby JoJo, including versions with different hairstyles, provided further support that there a range of possibilities existed for the defenfants’ character. All of this, plus testimony from the plaintiffs' expert, supported that “animators may choose to portray their babies with an amalgamation of realistic or unrealistic physical movements, distinctive behaviors, voices, and personalities.” So while “there may not necessarily be a gazillion ways … to depict an animated human baby,” there nevertheless was a “wide array of possible babies that would likely appeal to toddlers and parents.” This distinguished Baby JJ from other works where the courts found copyrights to be thin based on the limited range of expression available. See, e.g., Mattel, Inc. v. MGA Ent., Inc., 616 F.3d 904, 913 (9th Cir. 2010) (preliminary sculpt of dolls); Ets-Hokin v. Skyy Spirits Inc., 323 F.3d 763, 766 (9th Cir. 2003) (photo of vodka bottle); Satava v. Lowry, 323 F.3d 805, 812 (9th Cir. 2003) (glass-in-glass jellyfish sculpture).

Accordingly, the court held that the Baby JJ animated character was entitled to broad protection, and the jury was instructed to use the substantial similarity standard.

Moonbug Entertainment Limited v. BabyBus (Fujian) Network, No. 21-cv-06536-EMC, 2023 WL 4828363 (N.D. Cal. July 26, 2023)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/SearchServiceImages/2026-03-02-15-44-59-583-69a5b07bfe4ddbcd496d2bf1.jpg)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-28-23-34-09-665-69a37b71b4761ae8f05112dd.png)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-23-22-36-48-266-699cd680304bae27518b0c0e.png)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-23-22-32-15-805-699cd56f994bc9b52c44e804.png)