Plaintiff Steeplechase Arts & Production publishes musical instruction books, including Piano Book for Adult Beginners: Teach Yourself How to Play Famous Piano Songs, Read Music, Theory & Technique. The book - despite (or maybe because of?) its meandering title - is a powerhouse in its category: Rolling Stone ranked it among the very best, and (as of today) it has received 7367 reviews and achieved an aggregate 4.5 star rating on Amazon. Steeplechase registered trademark rights in the mark STEEPLECHASE ARTS & PRODUCTIONS for, among other things, musical instruction books.

Any pianist will tell you that a song book with a tight, glued binding can’t compare to one with a spiral binding that lies flat on the piano. Recognizing an unmet need, defendant Wisdom Paths, Inc. d/b/a Spiralverse purchased hundreds of copies of Steeplechase’s book, removed the original paperback glue bindings, punched holes in the pages, and installed spiral bindings. Voila! Build a better piano instruction book, and the world will beat a path to your door. Spiralverse sold the modified copies on Amazon Marketplace, presumably for a nice little profit. It also affixed to the front covers of some of the spiralbound books this label: “The original binding was removed and replaced with a spiral binding by Spiralverse.com.” Here are the books, side by side (image from the complaint):

All of this struck the wrong chord with Steeplechase, which sued Spiralverse for copyright infringement and unfair competition under the Lanham Act in New Jersey federal district court. Judge Kevin McNulty granted in part and denied in part the parties' pretrial cross motions for summary judgment.

Copyright

Steeplechase alleged that Spiralverse had infringed its copyright by creating and selling unauthorized derivative works – i.e., the spiral bound versions of its piano book.

Typically, a defendant that infringes upon a plaintiff's exclusive right to create derivative works (17 U.S.C. §106(2)) simultaneously will have infringed upon one or more of the plaintiff’s other exclusive rights under copyright. To take a famous example (and putting questions of fair use aside), when 2 Live Crew released its parody song “Pretty Woman,” the band not only created a derivative work based upon Roy Orbison’s original “Oh Pretty Woman”; it also violated Orbison’s reproduction rights (§106(1)) and distribution rights (§106(3)) when it sold copies of “Pretty Woman” (which allegedly was substantially similar to “Oh Pretty Woman”). Here, however, Spiralverse did not make any copies of Steeplechase’s song books, and the resale (i.e., distribution) of the books (at least unaltered versions of the books) would be protected under the first sale doctrine. (See 17 U.S.C. §109). Thus, Steeplechase's copyright claim turned on whether the rebound piano books qualified as derivative works under the Copyright Act.

A “derivative work” is defined as:

“a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgement, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted. A work consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or other modifications which, as a whole, represent an original work of authorship, is a “derivative work.”

Spiralverse argued that the rebound books were not derivative works because the second sentence of the definition requires that the resulting work be an “original work of authorship” – i.e., it must include new, original content sufficient to support an independent copyright. Since the spiral binding was (as Spiralverse put it) “a purely utilitarian element,” and since no original creative elements had been added, Spiralverse maintained that it had not created a “derivative work.”

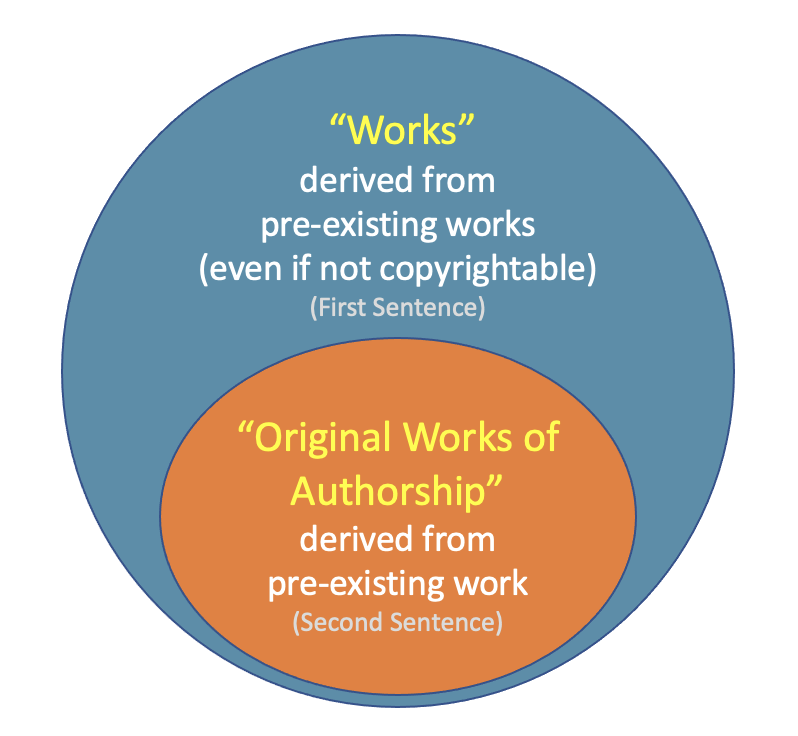

Naturally, Steeplechase viewed things differently. It argued that the definition’s first sentence broadly covers all “works” (an intentionally broad term) that are based on a pre-existing work, regardless of whether the resulting work is a copyrightable work of authorship. The definition’s second sentence, according to Steeplechase, merely clarifies that “original works of authorship” (which constitute a subset of the “works” referenced in the first sentence) also can fall within the definition. So, as interpreted by Steeplechase, the definition provides that "a 'work' is a 'derivative work' even if it constitutes 'an original work of authorship,' not only if it constitutes 'an original work of authorship.'” Here is a diagram (for those, like me, who live on the right side of their brains) of the interpretation urged by Steeplechase:

Steeplechase claimed that its reading was warranted because Congress intentionally had employed different terminology (the broad term “works” vs. and the narrower term “original works of authorship”) in each sentence, and to ignore the distinction would violate two cannons of statutory interpretation: (1) the presumption of consistent usage (a word or phrase is presumed to bear the same meaning throughout a statute, and a material variation in terms suggests a variation in meaning), and (2) the cannon of non-surplusage (if possible, every word and every provision in a statute is to be given effect, and a statute should not be interpreted in such a way that particular words add nothing or are meaningless).

The court found it unnecessary to enter this thicket of statutory interpretation, which has divided the circuit courts and commentators. Compare Lee v. A.R.T. Co. (7th Cir. 1997) (ceramic tiles on which copyrighted images were mounted did not constitute derivative works) with Mirage Editions, Inc. v. Albuquerque A.R.T. Co. (9th Cir. 1988) (reaching opposite conclusion). Instead, Judge McNulty put the question of originality aside and concluded that Spiralverse had not created a derivative work within the meaning of the Copyright Act because its spiral bound book was not “based upon” Steeplechase’s original; it was, instead, the very same book without the “recasting,” “transforming,” or “adapting” required by the definition of a derivative work. As the court put it:

“Although Spiralverse undoubtedly altered the Piano Books it purchased by installing spiral bindings, it did not “recast,” “adapt,” or “transform” the underlying work. To “recast” something is to remodel or refashion it so as to present it in a new way. See Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, “Recast.” Spiralverse did not make any changes to the content of the Piano Books so as to present the information in a different manner. To “adapt” something is to modify it for a new use. See Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, “Adapt.” The spiralbound books Spiralverse created and sold had the same use as the paperback versions manufactured by Steeplechase. Finally, “transform” implies a major change in form, nature, or function. See Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, “Transform.” Certainly Spiralverse did not work a major change to the Piano Books by modifying the binding. The only difference between a spiralbound and paperback version of the same book is the ease with which pages can be turned and material displayed." (Cleaned up.)

Accordingly, the court granted summary judgment to Spiralverse on the copyright claim.

False Advertising

Steeplechase also alleged in its complaint that Spiralverse had violated § 43(a) of the Lanham Act. because (1) it made the literally false claim that its books were “new” when they did not meet Amazon’s guidelines for what constitutes “new” merchandise or the common definition of the term “new,” and (2) Spiralverse had created the false impression that Steeplechase had authorized issuing the spiral bound copies of the book.

The court held that, based on the current record, it could not conclude that Spiralverse’s claim that the book was “new” was unambiguously false. “One could certainly argue that ‘new’ means ‘not altered in any manner after manufacturing,’ but one could also argue that ‘new’ simply means ‘not used.’” Moreover, Amazon apparently forces sellers listing products in Amazon Marketplace to describe the product as “new” or various different categories of “used.” None of the options accurately described a product (like the rebooks at issue here) that have not been used by a consumer but have been altered by a third-party seller. In a footnote the court noted that:

“If Amazon did not require a seller to choose between a fixed set of options and instead allowed the seller to describe the condition of a book using words of the seller’s choosing, I would be more inclined to find that Spiralverse’s listing was unambiguous and literally false. The record does not conclusively establish whether a seller has any flexibility in this regard.”

With respect to the false designation of origin claim, the court found that there was “insufficient evidence in the record to demonstrate that consumers likely understood that the rebinding was done without the permission of Steeplechase, or that consumers were likely confused about who was responsible.” Among other things, the parties disagreed as to whether Spiralverse’s label was affixed to all of the spiralbound books or only some. And because the parties did not include in the record images of covers of Spiralverse books with the label, “the Court [could not] determine for itself how conspicuous the label is.”

Steeplechase Arts & Productions, LLC v. Wisdom Paths, Inc., Civ. No. 22-02031 (KM)(MAH), 2023 WL 416080 (D. N.J. Jan 26, 2023)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-03-04-15-15-53-818-69a84ca9b468491d6513a290.png)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/SearchServiceImages/2026-03-02-15-44-59-583-69a5b07bfe4ddbcd496d2bf1.jpg)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-28-23-34-09-665-69a37b71b4761ae8f05112dd.png)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-23-22-36-48-266-699cd680304bae27518b0c0e.png)