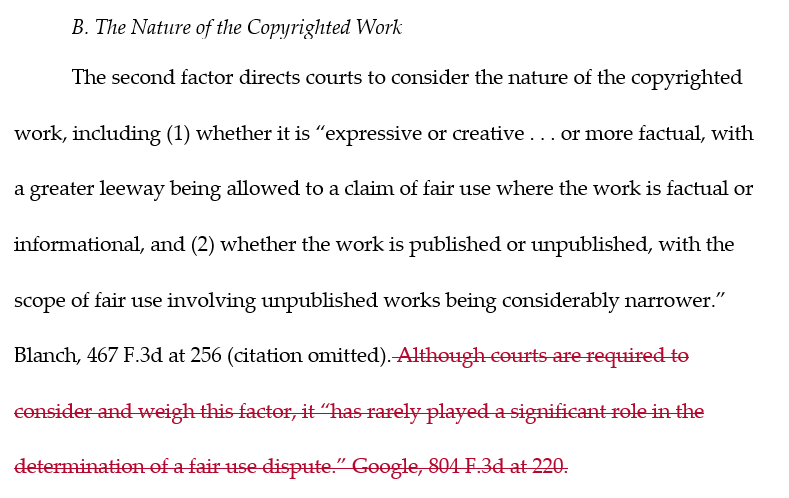

This is an update to our prior post on the Second Circuit's important fair use ruling in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 992 F.3d 99 (2d Cir. 2021). In that case, a panel of the Second Circuit held that (1) Andy Warhol's unauthorized use of a photo taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith to create and license a series of portraits of pop-icon Prince did not qualify as fair use as a matter of law, and (2) Warhol's series was substantially similar to (and infringed upon) the plaintiff's photograph as a matter of law.

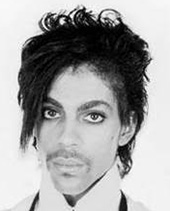

Here again is Goldsmith's photo:

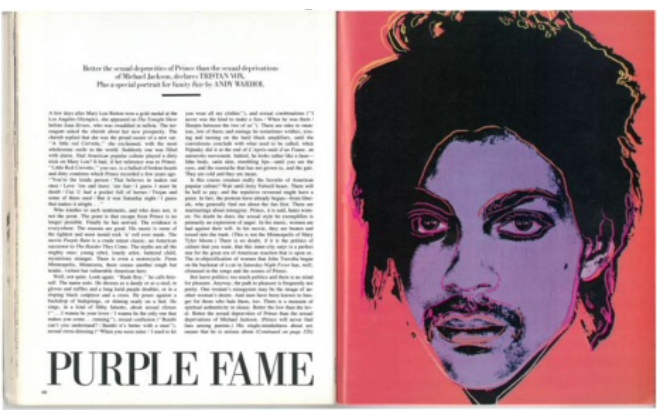

And here are some of the images created by Warhol:

The Andy Warhol Foundation ("AWF" or the "Foundation") petitioned the court for reconsideration in light of the Supreme Court's recent opinion in Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc.., 141 S. Ct. 1183 (2021). Last week, the Second Circuit panel granted the motion, withdrew its opinion of March 26, 2021, and issued a (slightly) amended opinion. (It also withdrew a concurring opinion by Judge Sullivan.) Unfortunately for the Foundation, the court left intact its prior holdings.

The modifications made by the court are subtle and few. Mere tweaks. Indeed, we needed to run a redline to catch the differences. But there were a few things that caught my eye.

First, a big question for all practitioners is what impact, if any, Google will have on fair use analysis in cases that involve works other than software like the declaring code at issue in that case. In its petition, the Foundation argued that Google "comprehensively refutes" the reasoning employed by the court in its initial Warhol opinion. The court disagreed, holding that Google merely reaffirmed that fair use analysis is "fact- and context-specific" and that "[l]ike the Supreme Court in Google, we [in Warhol] have applied those well-established principles to the particular facts before us to conclude that [the Foundation's] fair-use defense fails." Indeed, in the revised opinion, the court (at least to this reader) appeared to express skepticism that Google should have much impact on fair use cases involving creative works like those at issue in Warhol:

"The Court [in Google] repeatedly emphasized that "[t]he fact that computer programs are primarily functional makes it difficult to apply traditional copyright concepts in that technological world." Id. at 1208. If the application of traditional copyright concepts to "functional" computer programs is difficult, it follows that a case that addresses fair use in such a novel and unusual context is unlikely to work a dramatic change in the analysis of established principles as applied to a traditional area of copyrighted artistic expression. And indeed, the Supreme Court did not leave that conclusion to inference, expressly advising that in addressing fair use in this new arena, it "ha[d] not changed the nature of those [traditional copyright] concepts." Id."

Time will tell if other courts will agree with this assessment.

Second, in Google, the Supreme Court began its fair use analysis by doing a deep dive into the second factor (the "nature of the copyrighted work") - not the first! The Court concluded that the second factor weighed in favor of Google because, for a host of reasons, the declaring code at issue was “further than are most computer programs (such as the implementing code) from the core of copyright.” Many of us have wondered whether Google might breathe new life into the second statutory factor - often treated as a "non-factor" (or, you might say, the "Jan Brady factor") - in fair use decisions involving creative works. Perhaps.

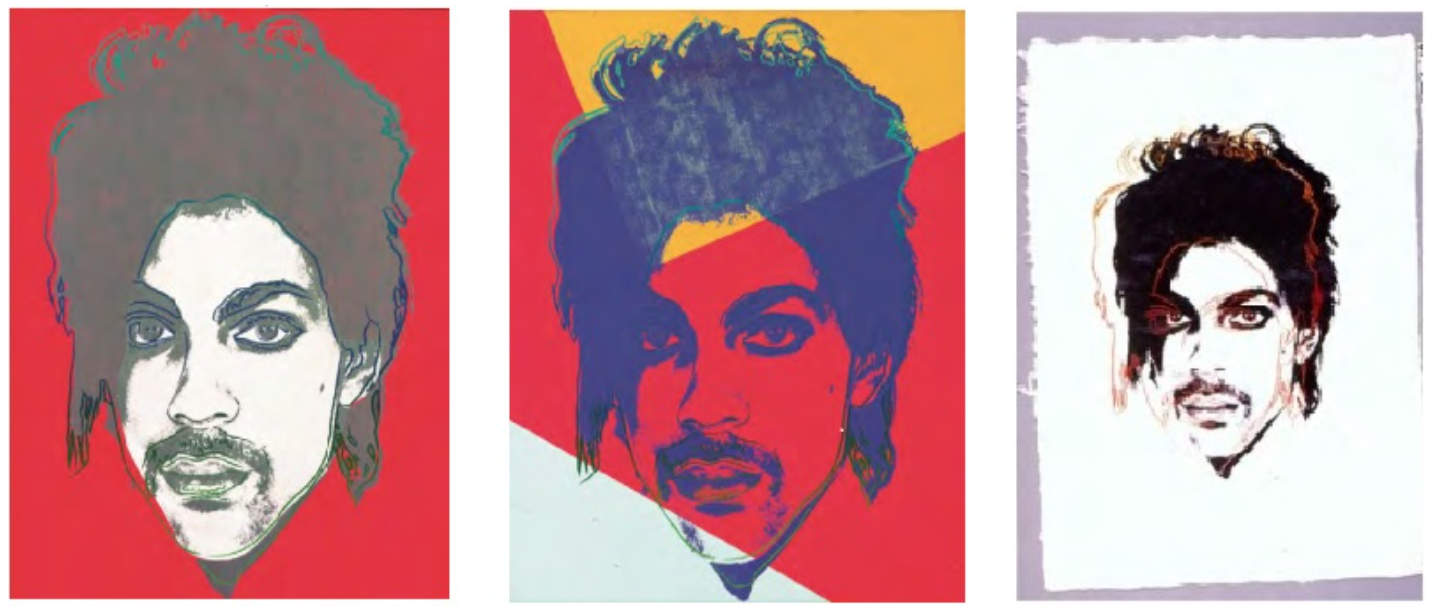

It is worth noting that in the amended Warhol opinion, the court made this subtle change in the section addressing the second factor:

Of course, this change can be explained as nothing more than a "citation scrub" - i.e., the removal of a citation to the Federal Circuit's opinion in Google that the Supreme Court reversed. However, the court easily could have substituted cites to numerous other decisions in which courts have noted that the second factor seldom adds much to the fair use analysis in cases involving creative works. Yet it didn't do so. Is this a subtle sign that the second factor will get more play in the future, even in cases involving creative, expressive works? Again, time will tell. See this post about Schwartzwald v. Oath, Inc., 2020 WL 5441291 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 10, 2020) (second factor favored fair use in case involving photo of actor and his girlfriend walking on streets of New York "as they naturally appeared” because the photo was "more factual in nature than creative").

Third, the court added a new footnote in connection with its discussion of the similarity between the purpose and function of Warhol's and Goldsmith's works (under the first statutory factor):

In other words, because a copyrighted logo has a different purpose and function than a celebrity portrait photograph (true enough), those of you lucky enough to own a Warhol Campbell's Soup print can relax. (At least for now.)

And, apparently, those of you lucky (I mean, rich) enough to own an original Warhol portrait of Prince, Marilyn, Jackie or anyone else also can relax. (Again, at least for now.) In his original (and in his updated) concurring opinion, Judge Jacobs wrote specifically to call out that the court's decision involved only the licensing of Warhol's artwork to a magazine, and it did not address the copyright status of the original works of Art created by Warhol:

"So, it is useful to emphasize that the holding does not consider, let alone decide, whether the infringement here encumbers the original Prince Series works that are in the hands of collectors or museums, or, in general, whether original works of art that borrow from protected material are likely to infringe."

Likewise, the revised majority opinion was supplemented to draw the same distinction between the original works of art by Warhol and commercially licensed uses of the same works:

"Moreover, what encroaches on Goldsmith’s market is [the Foundation's] commercial licensing of the Prince Series, not Warhol’s original creation. Thus, art that is not turned into a commercial replica of its source material, and that otherwise occupies a separate primary market, has significantly more “breathing space” than the commercial licensing of the Prince Series. Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579."

Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, __ F.3d __ (2d Cir. Aug. 24, 2021).

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/SearchServiceImages/2026-03-02-15-44-59-583-69a5b07bfe4ddbcd496d2bf1.jpg)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-28-23-34-09-665-69a37b71b4761ae8f05112dd.png)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-23-22-36-48-266-699cd680304bae27518b0c0e.png)

/Passle/5a0ef6743d9476135040a30c/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-23-22-32-15-805-699cd56f994bc9b52c44e804.png)